Selection rule

In physics and chemistry a selection rule, or transition rule, formally constrains the possible transitions of a system from one state to another. Selection rules have been derived for electronic, vibrational, and rotational transitions. The selection rules may differ according to the technique used to observe the transition.

Contents |

Overview

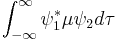

In quantum mechanics the basis for a spectroscopic selection rule is the value of the transition moment integral.[1]

where  and

and  are the wave functions of the two states involved in the transition and µ is the transition moment operator. If the value of this integral is zero the transition is forbidden. In practice, the integral itself does not need to be calculated to determine a selection rule. It is sufficient to determine the symmetry of transition moment function,

are the wave functions of the two states involved in the transition and µ is the transition moment operator. If the value of this integral is zero the transition is forbidden. In practice, the integral itself does not need to be calculated to determine a selection rule. It is sufficient to determine the symmetry of transition moment function,  . If the symmetry of this function spans the totally symmetric representation of the point group to which the atom or molecule belongs then its value is not zero and the transition is allowed. Otherwise, the transition is forbidden.

. If the symmetry of this function spans the totally symmetric representation of the point group to which the atom or molecule belongs then its value is not zero and the transition is allowed. Otherwise, the transition is forbidden.

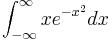

To understand the role of symmetry in determining whether the value of a definite integral is zero or not zero, consider the integral

The function y=x e-x2 is plotted at the right. It has the same form as the wave function of the first excited state of a harmonic oscillator. The (positive) area under the curve for x > 0 is equal to the (negative) area over the curve for x < 0. The sum of these two areas is zero; that is, the integral has a value of zero. This follows from the fact that the function is anti-symmetric in x; that is, y(-x) = -y(x). This argument can easily be extended to wave functions of more than one variable.[2]

The transition moment integral is non-zero if and only if the transition moment function,  , is symmetric in at least one variable, as when y(x) = y(-x). The symmetry of the transition moment function is the direct product of the symmetries of its three components. The symmetry characteristics of each component can be obtained from standard character tables. Rules for obtaining the symmetries of a direct product can be found in texts on character tables.[3]

, is symmetric in at least one variable, as when y(x) = y(-x). The symmetry of the transition moment function is the direct product of the symmetries of its three components. The symmetry characteristics of each component can be obtained from standard character tables. Rules for obtaining the symmetries of a direct product can be found in texts on character tables.[3]

| Transition type | µ transforms as | note |

|---|---|---|

| Electric dipole | x, y, z | Optical spectra |

| Electric quadrupole | x2, y2, z2, xy, xz, yz | Constraint x2 + y2 + z2 = 0 |

| Electric polarizability | x2, y2, z2, xy, xz, yz | Raman spectra |

| Magnetic dipole | Rx, Ry, Rz | Optical spectra (weak) |

Examples

Electronic spectra

The Laporte rule is a selection rule formally-stated as follows: In a centrosymmetric environment transitions between like atomic orbitals such as s-s,p-p, d-d, or f-f transitions are forbidden. The Laporte rule applies to electric dipole transitions, so the operator has u symmetry.[4] p orbitals also have u symmetry, so the symmetry of the transition moment function is given by the triple product u×u×u, which has u symmetry. The transitions are therefore forbidden. Likewise, d orbitals have g symmetry, so the triple product g×u×g also has u symmetry and the transition is forbidden.[5]

The wave function of a single electron is the product of a space-dependent wave function and a spin wave function. Spin is directional and can be said to have odd parity. It follows that transitions in which the spin "direction" changes are forbidden. In formal terms, only states with the same total spin quantum number are "spin-allowed".[6] In crystal field theory, d-d transitions that are spin-forbidden are very much weaker than spin-allowed transitions. Both can be observed, in spite of the Laporte rule, because the actual transitions are coupled to vibrations that are anti-symmetric and have the same symmetry as the dipole moment operator.[7]

Vibrational spectra

In vibrational spectroscopy, transitions are observed between different vibrational states. In a fundamental vibration, the molecule is excited from its ground state (v = 0) to the first excited state (v = 1). The symmetry of the ground-state wave function is the same as that of the molecule. It is, therefore, a basis for the totally symmetric representation in the point group of the molecule. It follows that, for a vibrational transition to be allowed, the symmetry of the excited state wave function must be the same as the symmetry of the transition moment operator.[8]

In infrared spectroscopy, the transition moment operator transforms as either x and/or y and/or z. The excited state wave function must also transform as at least one of these vectors. In Raman spectroscopy, the operator transforms as one of the second-order terms in the right-most column of the character table, below.[3]

| E | 8 C3 | 3 C2 | 6 S4 | 6 σd | |||

| A1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | x2 + y2 + z2 | |

| A2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | ||

| E | 2 | -1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | (2 z2 - x2 - y2,x2 - y2) | |

| T1 | 3 | 0 | -1 | 1 | -1 | (Rx, Ry, Rz) | |

| T2 | 3 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 1 | (x, y, z) | (xy, xz, yz) |

The molecule methane, CH4, may be used as an example to illustrate the application of these principles. The molecule is tetrahedral and has Td symmetry. The vibrations of methane span the representations A1 + E + 2T2.[9] Examination of the character table shows that all four vibrations are Raman-active, but only the T2 vibrations can be seen in the infrared spectrum.[10]

In the harmonic approximation, it can be shown that overtones are forbidden in both infrared and Raman spectra. However, when anharmonicity is taken into account, the transitions are weakly allowed.[11]

Rotational spectra

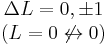

The selection rule for rotational transitions, derived from the symmetries of the rotational wave functions in a rigid rotor, is ΔJ = ±1, where J is a rotational quantum number.[12]

Coupled transitions

| Coupling in science |

|---|

| Classical coupling |

| Rotational–vibrational coupling |

| Quantum coupling |

| Quantum-mechanical coupling |

| Rovibrational coupling |

| Vibronic coupling |

| Rovibronic coupling |

| Angular momentum coupling |

| [edit this template] |

There are many types of coupled transition such as are observed in vibration-rotation spectra. The excited-state wave function is the product of two wave functions such as vibrational and rotational. The general principle is that the symmetry of the excited state is obtained as the direct product of the symmetries of the component wave functions.[13] In rovibronic transitions, the excited states involve three wave functions.

The infrared spectrum of hydrogen chloride gas shows rotational fine structure superimposed on the vibrational spectrum. This is typical of the infrared spectra of heteronuclear diatomic molecules. It shows the so-called P and R branches. The Q branch, located at the vibration frequency, is absent. Symmetric top molecules display the Q branch. This follows from the application of selection rules.[14]

Resonance Raman spectroscopy involves a kind of vibronic coupling. It results in much-increased intensity of fundamental and overtone transitions as the vibrations "steal" intensity from an allowed electronic transition.[15] In spite of appearances, the selection rules are the same as in Raman spectroscopy.[16]

Angular momentum

- See also angular momentum coupling

In general, electric (charge) radiation or magnetic (current, magnetic moment radiation) can be classified into multipoles Eλ (electric) or Mλ (magnetic) of order 2λ, e.g., E1 for electric dipole, E2 for quadrupole, or E3 for octupole. In transitions where the change in angular momentum between the initial and final states makes several multipole radiations possible, usually the lowest-order multipoles are overwhelmingly more likely, and dominate the transition.[17]

The emitted particle carries away an angular momentum λ, which for the photon must be at least 1, since it is a vector particle (i.e., it has JP = 1-). Thus, there is no E0 (electric monopoles) or M0 (magnetic monopoles, which do not seem to exist) radiation.

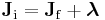

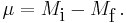

Since the total angular momentum has to be conserved during the transition, we have that

where  , and its z-projection is given by

, and its z-projection is given by  ;

;  and

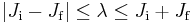

and  are, respectively, the initial and final angular momenta of the atom. The corresponding quantum numbers λ, μ must satisfy

are, respectively, the initial and final angular momenta of the atom. The corresponding quantum numbers λ, μ must satisfy

and

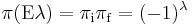

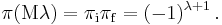

Parity is also preserved. For electric multipole transitions

while for magnetic multipoles

Thus, parity does not change for E-even or M-odd multipoles, while it changes for E-odd or M-even multipoles.

These considerations generate different sets of transitions rules depending on the multipole order and type. The expression forbidden transitions is often used; this does not mean that these transitions cannot occur, only that they are electric-dipole-forbidden. These transitions are perfectly possible; they merely occur at a lower rate. If the rate for an E1 transition is non-zero, the transition is said to be permitted; if it is zero, then M1, E2, etc. transitions can still produce radiation, albeit with much lower transitions rates. These are the so-called forbidden transitions. The transition rate decreases by a factor of about 1000 from one multipole to the next one, so the lowest multipole transitions are most likely to occur.[18]

Semi-forbidden transitions (resulting in so-called intercombination lines) are electric dipole (E1) transitions for which the selection rule that the spin does not change is violated. This is a result of the failure of LS coupling.

Summary table

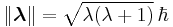

is the total angular momentum,

is the total angular momentum,  is the Azimuthal quantum number,

is the Azimuthal quantum number,  is the Spin quantum number, and

is the Spin quantum number, and  is the Magnetic quantum number. Which transitions are allowed is based on the Hydrogen-like atom.

is the Magnetic quantum number. Which transitions are allowed is based on the Hydrogen-like atom.

| Electric dipole (E1) | Magnetic dipole (M1) | Electric quadrupole (E2) | Magnetic quadrupole (M2) | Electric octupole (E3) | Magnetic octupole (M3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

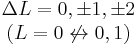

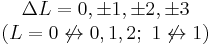

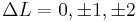

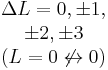

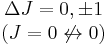

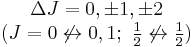

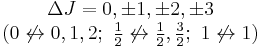

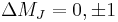

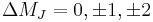

| Rigorous rules | (1) |  |

|

|

|||

| (2) |  |

|

|

||||

| (3) |  |

|

|

|

|||

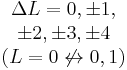

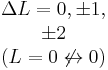

| LS coupling | (4) | One electron jump

Δl = ±1 |

No electron jump

Δl = 0, |

None or one electron jump

Δl = 0, ±2 |

One electron jump

Δl = ±1 |

One electron jump

Δl = ±1, ±3 |

One electron jump

Δl = 0, ±2 |

| (5) | If ΔS = 0

|

If ΔS = 0

|

If ΔS = 0

|

If ΔS = 0

|

|||

| Intermediate coupling | (6) | If ΔS = ±1

|

If ΔS = ±1

|

If ΔS = ±1

|

If ΔS = ±1

|

If ΔS = ±1

|

|

See also

Notes

- ^ Harris & Berolucci, p. 130

- ^ Harris & Berolucci, p. 79

- ^ a b c Salthouse, J.A.; Ware, M.J. (1972). Point group character tables and related data. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521081394.

- ^ Anything with u (German ungerade) symmetry is antisymmetric with respect to the centre of symmetry. g (German gerade) signifies symmetric with respect to the centre of symmetry. If the transition moment function has u symmetry, the positive and negative parts will be equal to each other, so the integral has a value of zero.

- ^ Harris & Berolucci, p. 330

- ^ Harris & Berolucci, p. 336

- ^ Cotton Section 9.6, Selection rules and polarizations

- ^ Cotton, Section 10.6 Selection rules for fundamental vibrational transitions

- ^ Cotton, Chapter 10 Molecular Vibrations

- ^ Cotton p. 327

- ^ Califano, S. (1976). Vibrational states. Wiley. ISBN 0471129968. Chapter 9, Anharmonicity

- ^ Kroto, H.W. (1992). Molecular Rotation Spectra.. new York: Dover. ISBN 048649540X.

- ^ Harris & Berolucci, p. 339

- ^ Harris & Berolucci, p. 123

- ^ Long, D.A. (2001). The Raman Effect: A Unified Treatment of the Theory of Raman Scattering by Molecules. Wiley. ISBN 0471490288. Chapter 7, Vibrational Resonance Raman Scattering

- ^ Harris & Berolucci, p. 198

- ^ Softley, T.P. (1994). Atomic Spectra. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198556888.

- ^ Condon, E.V.; Shortley, G.H. (1953). The Theory of Atomic Spectra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521092094.

References

Harris, D.C.; Bertolucci, M.D. (1978). Symmetry and Spectroscopy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198551525.

Cotton, F.A. (1990). Chemical Applications of Group Theory (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-51094-9.

Further reading

- Stanton, L. (1973). "Selection rules for pure rotation and vibration-rotation hyper-Raman spectra". Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 1 (1): 53–70. Bibcode 1973JRSp....1...53S. doi:10.1002/jrs.1250010105.

- Bower, D.I; Maddams, W.F. (1989). The vibrational spectroscopy of polymers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 24633 4. Section 4.1.5: Selection rules for Raman activity.

- Sherwood, P.M.A. (1972). Vibrational Spectroscopy of Solids. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 08482 2. Chapter 4: The interaction of radiation with a crystal.